“Dad, check out this game I made in Python!”

A few weeks ago, my eldest son Diego (19) told me with pride:

“Dad, check out the game I made in Python!”

He explained that it was an assignment from his Introduction to Programming course at university. And with a smile, he confessed that actually, the task was much simpler: to write code that included more than one class, and for one of the classes to call functions from the other class.

“But that was too easy, it was no challenge! So, I wanted to do something more fun: let me introduce you to my maze game!”

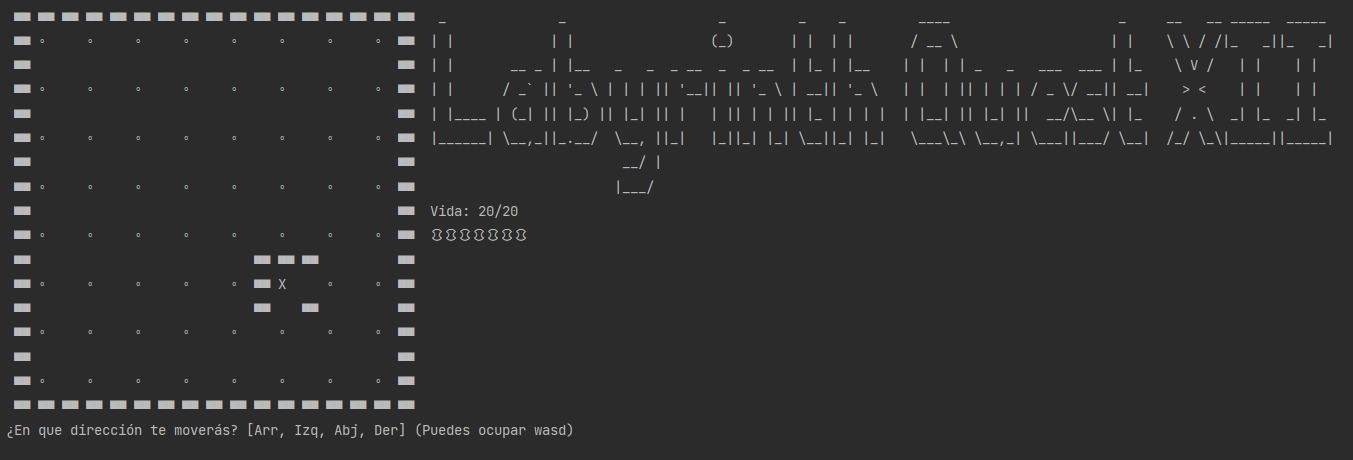

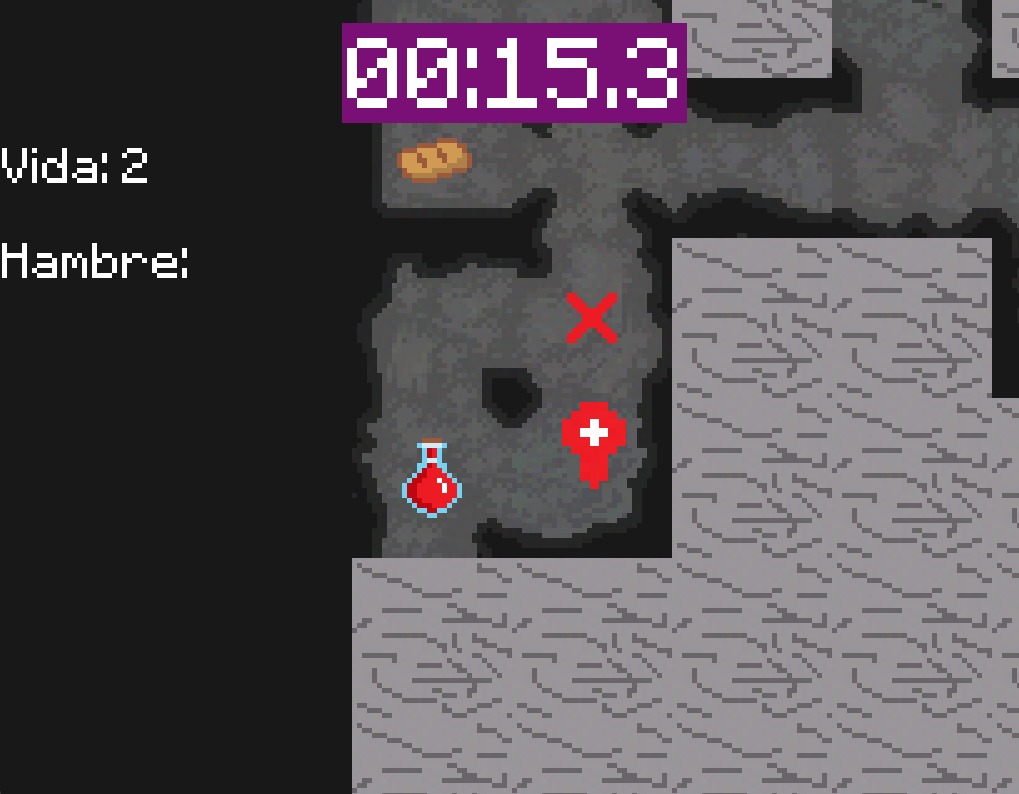

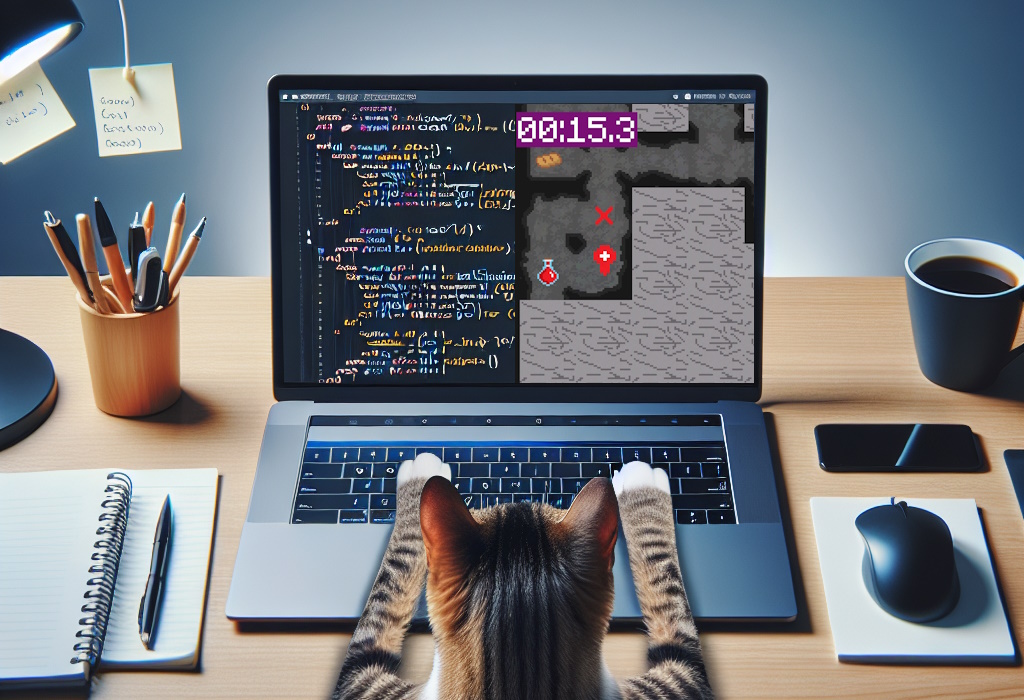

Curious, I sat down in front of his computer. Diego started the program and I faced the first screen:

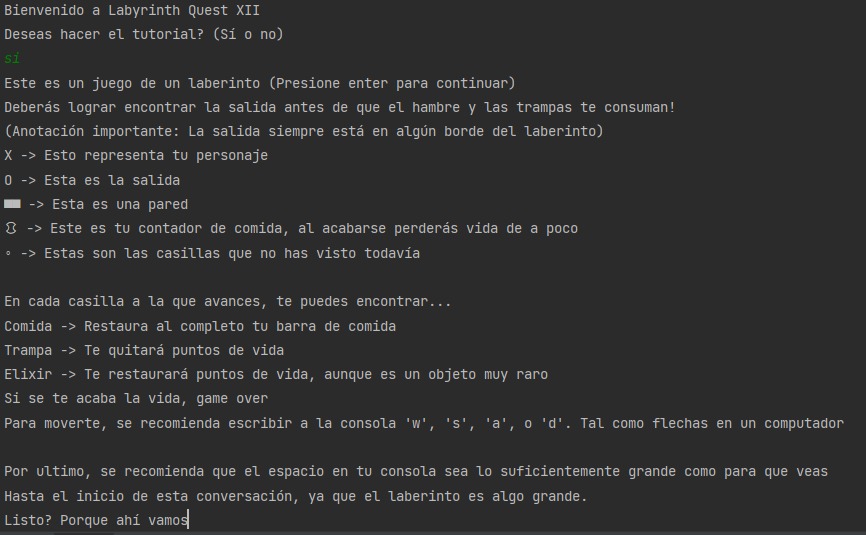

It was clear that Diego was very motivated, not only by his eagerness for me to see his project but also by the details I could see in the first few minutes of the game. From the name he chose to the tutorial teaching the player the rules of the game, it was evident he put a lot of effort into the result:

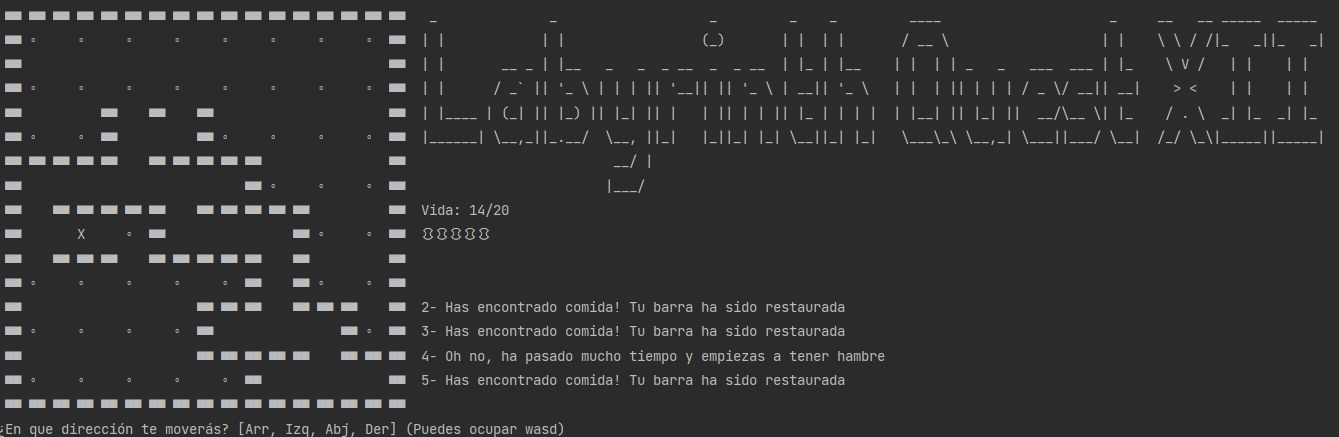

After going through the instruction phase, I began to navigate the maze in search of the exit. I was surprised to find that the game implemented several systems; it wasn’t just a matter of reaching the goal.

For example, the player has a certain amount of energy and needs to recharge by finding food in the maze before running out. Plus, there’s a “fog of war” system, which isn’t trivial to implement. This mechanic, widely used in video games, involves hiding unexplored areas of the map until the player traverses them.

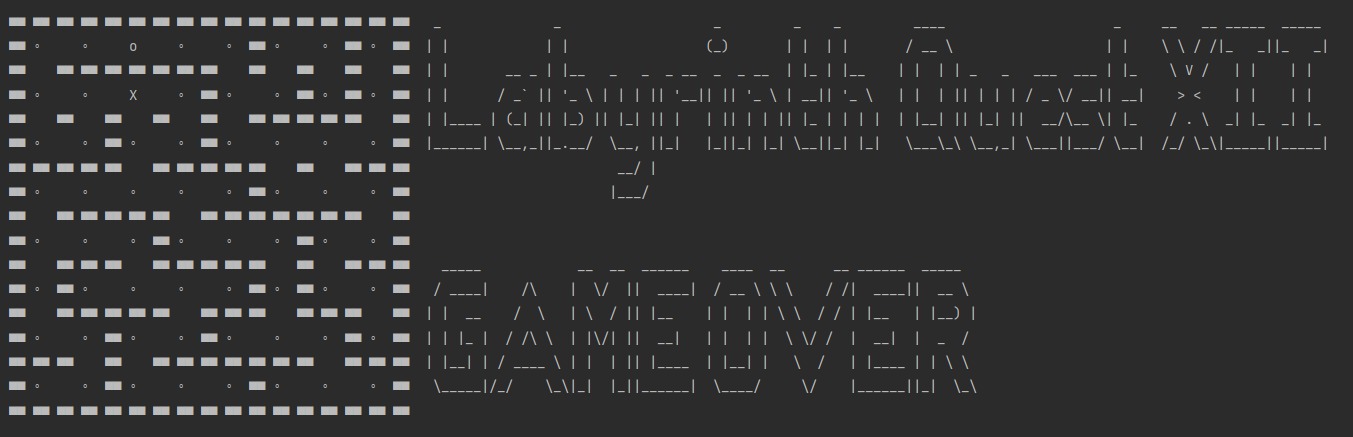

I made several attempts, losing most of them by running out of energy and only reached the exit once. I had a lot of fun, not only because of the game itself (I think it’s quite challenging!), but because I enjoyed playing a creation fully programmed by Diego.

Dreams, motivations, and interests

Many years ago, when I started this blog, my very first article was about how Diego had said in school that “When I grow up, I want to be a Videogame Creator”.

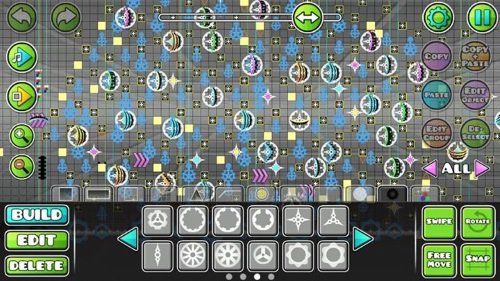

Over the following months and years, he held on to that idea and even dabbled in Level Design, a discipline of video game development, creating levels for games like Geometry Dash.

Often, during that time, I wanted to encourage him and bring him closer to video game development. But I also wondered if I might become one of those parents obsessed with their child following in their footsteps, not letting them explore and find their own path. Meanwhile, Diego started to get bored with level design and became interested in other things.

Around the same time, I discovered the Hour of Code initiative and tried to encourage him to learn programming through its activities. I also bought some mini robots from Wonder Workshop which are designed to stimulate programming learning in kids. They caught his attention, but he wouldn’t engage with them for more than a few minutes.

When he got a little older, he mentioned again that he wanted to learn to program and I offered to teach him. I gave him a few lessons in C#, thinking it was clear enough (compared to other languages like C++) to learn the basics, and it was the one I was most familiar with in recent years. We did a few small things, I assigned him some tasks which he tackled diligently, but the spark to learn more on his own never really ignited.

Years passed, and his interests continued to evolve. He started to like science, especially physics. He dove deeper into that world, watching videos of scientists, reading articles and books, and discussing scientific topics at family meals.

As he approached the last years of school, I dared to ask if he had any idea what he wanted to study at university. He said he wasn’t sure yet, but he thought it would probably be something related to Physics. The childhood dream of becoming a video game creator had been left behind.

I decided not to push him anymore with programming or video games. Perhaps he would find his own motivation in the future.

A new motivation

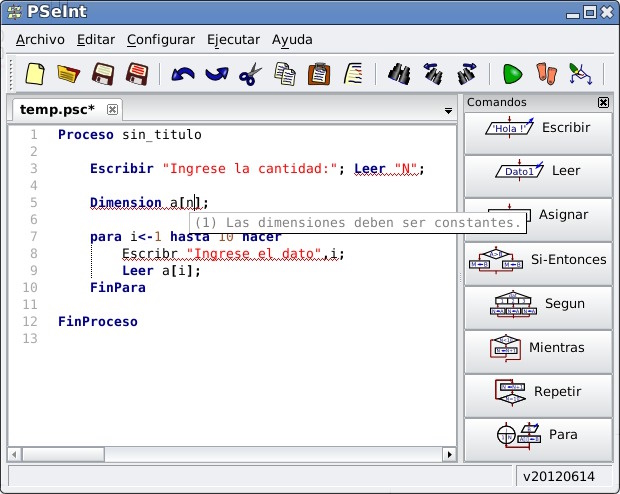

In his final year of high school, that motivation arrived. Diego had to choose some elective courses, and he opted for one in Programming. There they started teaching him the basics, just as I had years before. But instead of using C#, they used PSeInt, a language I didn’t even know. It’s a very simple and didactic language, designed specifically for teaching programming.

Diego took the course with a friend, and together they motivated each other to learn more than what the teacher instructed. Later, they were taught the basics of Python and there, with a more powerful tool at their disposal (compared to PSeInt), their motivation increased.

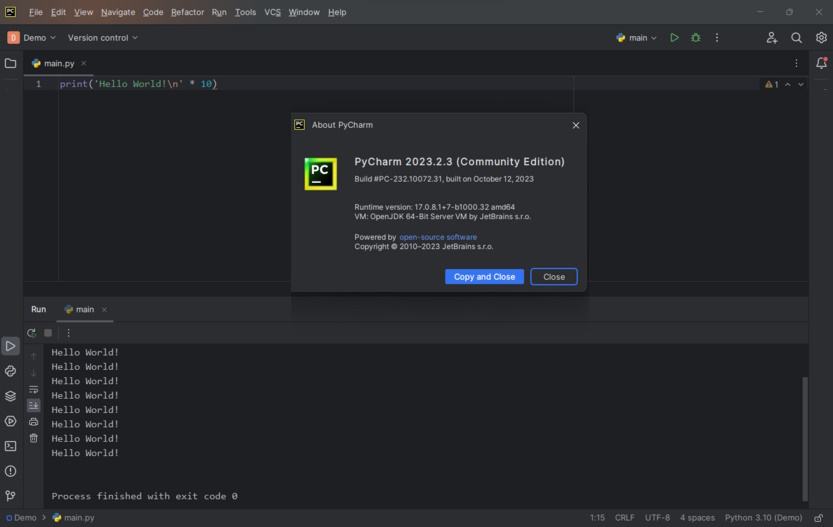

He first learned the basics and then, with his friend, they put together a couple of very simple games, ranging from “Tic Tac Toe” (or “Cat’s Game,” as we know it in Chile) to a very basic type of “Pokemon” using the PyWin library. They also learned to use PyCharm, one of the most popular Python editors on the market.

This year, now in his first year of university, he was taught Python again in his Introduction to Programming course. With all the experience and motivation from the previous year, he dared to take on more interesting challenges, which led him to the game he proudly showed me.

But he didn’t stop there. In recent weeks, along with a friend who is also very motivated by the subject, they are remaking Diego’s game using the Godot game engine. It includes its own programming language called GDScript which is, at least in appearance, very similar to Python.

Diego hasn’t abandoned his idea of wanting to work in Physics. For him, programming and his video game under construction are entertaining and challenging hobbies.

For my part, I’m happy that he learned to program, as it’s a tool that will serve him in any profession. And of course, I also enjoy seeing that he likes creating video games, even if just as a hobby. I am looking forward to the Godot version of Labyrinth being ready, and to seeing what inspires him next!

Does anyone else know about PSeInt? Any Godot experts out there who can recommend resources for Diego?

Juan Pablo makes videogames since he was 8 and he is a father since 2004. Today, he has three children and he has worked in more than 20 videogames. He got interested on how paternity and the videogame industry are related and he decided to write about it, founding "Papa Game Dev".

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *