“Dad, I want to learn how to code!”

Almost thirty years ago, my dad shown me two written lines on the TV screen that was connected to our Atari 800 XL.

10 PRINT "HOLA"

20 GOTO 10He told me that those were two lines of code and he invited me to watch what happened when he told the computer to “run” that code. Astonished, I saw “HELLO” started to be unceasingly written on the screen:

HOLA

HOLA

HOLA

HOLA

HOLA

HOLA

HOLAI asked my dad how did he do that, and he explained me that programming code was made up of a series of instructions that the computer was able to understand and follow. My dad looked more powerful than “He-Man”, “Lion-O” and “The Avenger” altogether (if you don’t know them, they were all cartoon super heroes that we watched in Chile during the 80s).

I wanted to know how my dad had learned to tell things to the computer, so he explained me that he knew how to code, and because of that he knew how to tell the computer what to do in a language that the machine would understand.

A wonderful idea crossed my mind. I already knew some videogames and I really loved them. I dared to ask:

“If I learn how to code, will I be able to make videogames?”

“Yes son, videogames are also made with code.”

“So dad, I want to learn how to code!”

Since then, my strongest motivation for learning how to code was the huge admiration I had for the few videogames I knew. At the beginning, I learned Atari “Basic” language, either with my dad’s guide or by copying code from some magazines he brought home.

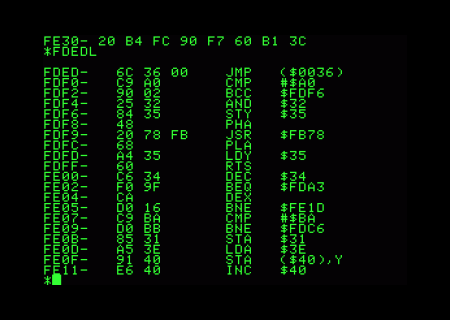

Some months later, I realized that there were a lot of videogames on the Atari that seemed to do stuff that I was not able to do with Basic. So, my father explained me that there were a lot of programming languages. Some were simpler while others were much more complex. The former were designed to help people code simpler programs fast, while the later were designed to do more powerful programs, but in a more complex way.

Motivated by the challenge, I learned “Assembler” on the Atari and then “Pascal” and “C” on a mighty (at that time) 40 MHz 386 PC. I still remember how amazing was the freedom I felt while writing hundreds of lines of code and how much I enjoyed watching my programs run.

By the time I finished school, I had written several thousands of lines of code in about five different programming languages, and I had completed around ten small videogames plus some small apps that I used as training exercises.

And all started with a flash of inspirtation: those two lines of code and the magic of watching them run.

What is coding?

Many people think that coding is some kind of occult science or something like the matrix in “The Matrix” movie. Something that only the chosen one can understand and master, like Neo, the main character in “The Matrix”.

Fortunately, coding is easier than that.

Putting it simply, to code is to give instructions to a computer using a language that the machine can understand.

Everything that works on a computer, from the simplest to the most complex, is a program made with code. And every program was coded by somebody, using some programming language.

There are a lot of programming languages, hundreds, and several ways to classify them. High level or low level languages, functional, structured or object oriented languages, are just a few samples of programming language types.

Some programming languages are very simple because they were created to solve very basic tasks and anyone can learn them in just a few minutes. On the other hand, there are other programming languages that are much more complex and that require the coder to be trained and specialized for a significantly longer period in order to master them.

Most programming languages were created with a particular purpose in mind, such as solving math problems, programming complex systems or teaching code to kids.

There are also programming languages that were conceived to add features that could be lacking in other languages. In that case, the new language is an evolution of the older one. For instance, the C++ language, one of the most powerful and popular, is an evolution of the C language, also very popular. C++ also has “descendants”, such as the C# language which is used a lot nowadays.

And we are not only talking about programs that run on computers like a “PC” or a “Mac”.

Programming code is present in every “smart” electronic device, because every function on them is also a computer program. From a washing machine to a brand new refrigerator; from a scientific calculator to a modern telescope in an observatory; from a smart phone to a videogame console.

All of them were coded using some programming language.

Learning to code with a turtle

One of the most didactic programming languages ever made is Logo. Created around half a century ago and currently maintained by a nonprofit organization called the Logo Foundation (website), it’s still used nowadays to show kids all over the world the basics of coding.

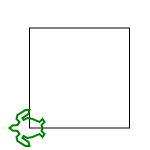

In Logo, the coder gives instructions to a turtle that leaves a trail (a line) when it moves. In its most basic version, there are only a few simple instructions that tell the turtle to move forward or backwards a certain distance, and also to turn right or left a certain amount of degrees.

For example, the following code in Logo draws a square in the computer screen, each side having 100 units long:

forward 100

right 90

forward 100

right 90

forward 100

right 90

forward 100The code is made exclusively of instructions that tell the turtle to move “forward” and to turn “right”. First, we instruct the turtle to move forward 100 units, then to turn right 90 degrees, then to move forward 100 units again, etc., until we complete four lines that form a square.

The Logo interpreter (a program that understands Logo and executes the instructions) follows every step one after the other, from the first one to the last one. Same than other programming languages, Logo has some special instructions to allow repeating a group of steps. For instance, the code to draw a square can also be written in a simpler way:

repeat 4 [

forward 100

right 90

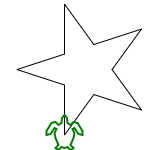

]Anyone could say that Logo is a “toy language” and that it can only be used to draw simple figures. But with some imagination, and combining the simple instructions in a clever way, you can actually draw amazing stuff. The following code draws a star and it has only two more instructions than the one that draws a square, plus an extra starting line to clear the previous drawing:

clearscreen

repeat 5 [

forward 50

left 72

forward 50

right 144

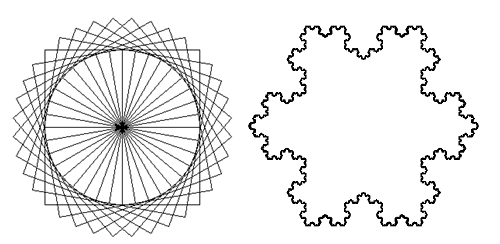

]If you have enough patience and write longer and more complex code, it’s possible to get impressive designs:

I encourage you to try these small programs yourself or try any code you like. There are a lot of Logo interpreters that can be used directly in a website, like this at Calormen (website) or this other one at Transum (website). Anybody can get there and start to code in Logo right away. Give it a try and you will be starting to code!

Speaking the language of the future

Hundreds of years ago, reading and writing was a privilege of the educated elite. Most of the population did not even need to know such things in order to perform their occupations. Obviously, the reality has changed a lot and reading and writing is very important for most professions: learning a language is now considered a fundamental part of education all over the world.

Similarly, many of us believe that coding will be key for the future generations and that coding will be “the language of the future”. In ten, twenty, thirty or fifty more years, our children and grandchildren will face challenges that we can’t even imagine, but it’s very likely that most of them will require them to understand how to use technology.

Hence, knowing how to code, understanding how to give instructions to a machine and how to take advantage of that potential for their professional (and even personal) lives will be essential for future generations.

Now is the time to start giving those tools to our children.

That’s the reason that is pushing a lot of people to advocate for coding to be taught at every school. Nonprofit organizations, universities, influential people, foundations, even some governments, they are all raising their voices and talking about this.

An Hour of Code

In this context, an initiative called the “Hour of Code” was created by Code.org (website). Its objective is to generate a global movement in which, during the same week, as much kids as possible learn the basics of coding during at least one hour.

Inspired by the experience, many of those kids will get motivated and will start to get curious for technology, seeking new ways to learn and get better on their own.

Last year, the Hour of Code (website) got more than ten million kids to participate in the initiative. During this year, even more kids have already tried the lessons and tutorials in their website.

Of course, the Hour of Code will be held again this year, with an even more ambitious goal and a much broader media reach. During the week of December 7th to December 13th, the expectation is to get a hundred million kids to try an hour of code around the globe.

In Chile, another nonprofit organization called Kodea.org also organized a local version of the Hour of Code. They convened several academic, public and private institutions and organized “La Hora del Código Chile” (The Chilean Hour of Code, website), coordinating their efforts with other Latin-American countries and under the guidelines of the global event owner.

During the week of October 5th to October 11th, almost a thousand schools along the country joined the initiative, with more than twenty thousand total participants. A very nice result considering it was the first time that the event had local organizations support.

It’s important to clarify that none of those kids will actually get enough knowledge during that single hour to become a professional coder or to be able to create applications or videogames. But that’s not the goal anyway.

The main goal is to give them the chance to get that flash of inspiration, such as the one I had thirty years ago thanks to my dad.

The goal is to show them what is coding about, to let them discover that computers understand orders if the correct instructions are used. Many will feel that it’s interesting, maybe even fun, but they won’t get much farther. But some others will get inspired by the experience and they will get motivated to learn more and to do more complex programs.

And regardless of how much they continue to learn, the most important thing is that all of them will have an idea of “What is to code?”, even if it was a short fun experience. That tiny seed will make a difference years later.

I invite you all to participate in the Hour of Code. If you have kids, share with them the website and encourage them to participate. If you are a teacher, hopefully you will be able to run an Hour of Code with your students. And, in any other case, you can support the initiative by spreading the word with your friends, contacts and in social networks.

We can all be part of this. We can all put our two cents in this, to provide our children with the tools they will need in their future.

Because their future is our responsibility.

More information about how to participate in the Hour of Code in their website.

Juan Pablo makes videogames since he was 8 and he is a father since 2004. Today, he has three children and he has worked in more than 20 videogames. He got interested on how paternity and the videogame industry are related and he decided to write about it, founding "Papa Game Dev".

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *